The Inquisitor in the kitchen with a spit !

10 JANUARY 2016 | PAR SOPHIE RAOBEHARILALA

To many of us, Inquisition recalls dark times of the Spanish Inquisition with its atmosphere of terror, torture and denunciation. If the Spanish preferred to follow a rather extreme form of justice, Malta on the other hand opted for a less radical approach, meaning that being summoned at the Inquisitor’s palace was not synonym of sure death.

The accused in this case is the position of Inquisitor. In 1574, the office of the bishop and inquisitor were separated for the first time. However the Inquisitor was a representative of the Curia and was entitled to have his own jurisdiction.

The role of the Inquisitor was to preside the Inquisition Tribunal and judge with the help of his collaborators. Despite being responsible for the custody of the Faith, he was also the official representative of the pope in Malta. In that respect he received his orders from the Supreme Congregation which sent its instructions on his behaviour and way of life.1 The Inquisitor’s palace was therefore expected to follow a strict lifestyle in his actions as well as in his diet. Through this investigation, we will try to identify the crime of greed, the motive.

❖ Food

But first let’s have a look at the means, food supplies on the island during the Renaissance. Malta’s food resources were very limited thanks to the various events the island faced over 200 years, including wars and diseases. Grain was the base of meals, and it is the ingredient which suffered the most in these circumstances. Harvest was poor in quantities and despite it being enough to feed the entire population, it would only be sufficient for half a year.2 Malta therefore had to import grain from Sicily, island with which strong links had been created during the Ottoman Empire’s invasion, links which remained basic for the economic and political survival of Hospitaller Malta. However, Sicily hadn’t been spared by these same events. As sources point out:

“Antonio Pignatelli’s years in Malta after 1646 were marked by serious famine and poverty among the local population caused by a dearth in Sicily which used to provide the islands with all types of food provisions. Inquisitor Pignatelli himself wrote to Rome to plead on behalf of the Maltese but received no positive answer. Acting on his own responsibility as the head of the Reverenda Fabbrica of St Peter which had in custody the pious legacies of the diocese of Malta, he offered its moneys for food provisions until the situation improved when the money had to be returned.”3

In addition to Italian importations, supply of provisions was also due to European merchants’ trade as well as Maltese expatriates:

“Maltese working abroad were doing merchandising between Malta and other countries (France, Spain, Portugal, Italy)”4. The Inquisitor’s Palace supplied as well with the merchants:

“However, we are informed that Gio. Andrea Debono was distillor of acque ardenti at Almeida in Lisbon, […]. There is uch more evidence about wares that these merchants imported into Malta, […]cooks […]. The Reggimento di Malta consisted of recruits from several foreign countries. […] Some were in the service of the inquisitor […]”.5

The Knights of the Order were established in auberges in Birgu and later in Valletta. Their meals were following specific regulations yet because of their social rank, standards were kept:

“Knights from central and northern Europe seldom took well to the Mediterranean lifestyle. Especially as regards dress, food, and drinks, they generally kept to their old habits. This meant that they needed their own cooks and a regular supply of foreign ingredients.”6

The supply of foreign ingredients and products was therefore assured in Malta.

With regards to dairy products, cheese was consumed at both ends of the social scale. The most common cheese in Malta would be goat cheese, as described in de Soldanis’ meal, :

“Gobon is today translated as cheese but Soldanis serves gobna which is a type of goat cheese ġbejniet, usually eaten mature for a better taste. Soldanis explains he saw this cheese sold in Italy under the name Maltese Cheese (formaggio maltese) which was preserved in a herb called hhascise e rihh (well pellitory), kept in white wine and left to set in a humid place for fifteen to twenty days, making it cheese for those who have a delicate palate. Kassata accompanied cheese, which is a small pie filled with cheese and eggs or filled with vegetables, meat or fish”.7

Another source mentions this Sicilian cheese as being consumed by all. However, English cheese was also largely available. Parmesan, Swiss and Dutch cheeses were more of a high society delicacy.

If grain was a base of Maltese diet, meat was also part of meals although not consumed regularly. Rabbit and birds, lamb, goat and pork were consumed. As an account from Louis Boisgelin mentions, the Maltese diet was very simple and healthy:

“[…] the Maltese had a special preference for spiced dishes and for pork. Their favourite dishes were fish, lamb, vegetables, fruits and game birds […]”.8

And again,

“[…] Roland de la Platire observed that the Maltese liked to eat rabbit meat and all species of game birds very much. That the Maltese farmers were fanatic hunters of rabbits had been observed by several eighteenth-century travellers.”9

Meat, especially game, was therefore regularly served at upper-class tables as the price would be high.

With regards to fish, this account mentions a regular consumption of fish around the island. However other sources following this conclusion, point out the lack of fish supplies around the Maltese coasts:

“In the later part of the seventeenth century, tuna fishing seemed to have died out […]. The Inquisitor Borromeo noted in his report on Malta sent to Rome in late 1654 that in the middle of the seventeenth century most of the Maltese fishermen and sailors were in a miserable quarter of Birgu. […] Since the Maltese coast did not abound in fish, as Alexandre Bisani had observed in 1788, the Maltese even sailed as far as the island of Galita to fish and obtain corals.”10

❖ Architecture and furnishing

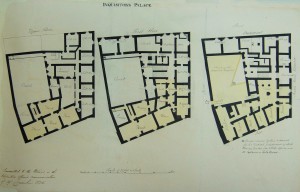

During the Order of Saint John’s presence in Malta, sixty inquisitors have been nominated to survey the propagation of heresy, sorcery and blasphemy. The Inquisitor’s palace hosted these representatives. The building comprised the Inquisitor’s apartments, a prison and the tribunal, as well as guests apartment and a service’s quarter. As the inventories illustrate, the Inquisitor used to host visiting guests from Grand Tours as well as great receptions. Over the period of 1700-1798, the kitchen area transformed from being divided into fifteen rooms to seven main rooms. The initial layout included kitchen, pantry and service quarters, rooms which remained at least until 1798. When comparing inventories from 1759 and 1798, the recurrent utensils for food preparations were copper and terracotta pots and pans, fish poachers, cauldrons, tart pans and spits. Three noteworthy elements also brought forward were ice-cream churns, butcher’s knife, and many cake moulds. We can therefore presume that meals were prepared from scratch at the palace, with meat cut on site. Preparation techniques varied from boiling, frying, roasting, baking, freezing. With regards to food itself, again inventories stress out the consumption of meat roasts and meat stews, large fishes, sauces and soups, cheese, olive oil, various types of sweet and savoury pastries, milk, chocolate and coffee.

During the Order of Saint John’s presence in Malta, sixty inquisitors have been nominated to survey the propagation of heresy, sorcery and blasphemy. The Inquisitor’s palace hosted these representatives. The building comprised the Inquisitor’s apartments, a prison and the tribunal, as well as guests apartment and a service’s quarter. As the inventories illustrate, the Inquisitor used to host visiting guests from Grand Tours as well as great receptions. Over the period of 1700-1798, the kitchen area transformed from being divided into fifteen rooms to seven main rooms. The initial layout included kitchen, pantry and service quarters, rooms which remained at least until 1798. When comparing inventories from 1759 and 1798, the recurrent utensils for food preparations were copper and terracotta pots and pans, fish poachers, cauldrons, tart pans and spits. Three noteworthy elements also brought forward were ice-cream churns, butcher’s knife, and many cake moulds. We can therefore presume that meals were prepared from scratch at the palace, with meat cut on site. Preparation techniques varied from boiling, frying, roasting, baking, freezing. With regards to food itself, again inventories stress out the consumption of meat roasts and meat stews, large fishes, sauces and soups, cheese, olive oil, various types of sweet and savoury pastries, milk, chocolate and coffee.

When comparing these inventories elements with the food supplies available in Malta at the time, it is possible to retrace examples of an Inquisitor’s plate.

Taking a close look to the ground floor’s layout, 2 ovens and a fireplace can be located in three different rooms, each interconnected and potentially existing going back to the 18th century. Furthermore, the use of ‘Dutch ovens’ and hobs is mentioned in the inventories. We can therefore presume that the kitchen hosting the fireplace would be the room were roasts were prepared. About 6 to 7 spits of various sizes are mentioned in the inventories. Since the palace was only hosting prisoners on one side, and the Inquisitor and his retinue on another, both groups having to follow a strict diet (voluntarily or not), it is fair to say that this great number of spits was used for diner receptions at the palace. The number of pastry moulds and cutters added to the various ovens, point out the sophistication of served meals. The presence of ice-cream churns, coffee grinder and chocolate pots finish to assign a rather refined and delicate palate to the Inquisitors who seem to have tastes influenced by the radiant Italian and French cuisines.

Taking a close look to the ground floor’s layout, 2 ovens and a fireplace can be located in three different rooms, each interconnected and potentially existing going back to the 18th century. Furthermore, the use of ‘Dutch ovens’ and hobs is mentioned in the inventories. We can therefore presume that the kitchen hosting the fireplace would be the room were roasts were prepared. About 6 to 7 spits of various sizes are mentioned in the inventories. Since the palace was only hosting prisoners on one side, and the Inquisitor and his retinue on another, both groups having to follow a strict diet (voluntarily or not), it is fair to say that this great number of spits was used for diner receptions at the palace. The number of pastry moulds and cutters added to the various ovens, point out the sophistication of served meals. The presence of ice-cream churns, coffee grinder and chocolate pots finish to assign a rather refined and delicate palate to the Inquisitors who seem to have tastes influenced by the radiant Italian and French cuisines.

❖ Verdict

The palace hosted a succession of Inquisitors, each of them with their own vision of strict lifestyle. In light of these discoveries, we can come to the conclusion that in general, inquisitors had a rather European diet with meals based on local and imported ingredients. The standards remained high over the period, with a cuisine including fine delicacies and following the European high cuisine novelties despite being on an island. Was it to maintain a respectful image due to a controversial position in Maltese society11, or was it rather to keep ounces of a past lifestyle, the answer to that question depends on a personal vision of the role and the degree of frivolity each Inquisitor possessed. The richness of the Inquisitor’s table was more in product quality rather than in the quantities, yet it was still seen as a feasting place, which in contrast with the rest of the population’s diet, would appear to be indecent and far from a supposed lean regime. In that respect, Inquisitors were found guilty of greediness and pomp.